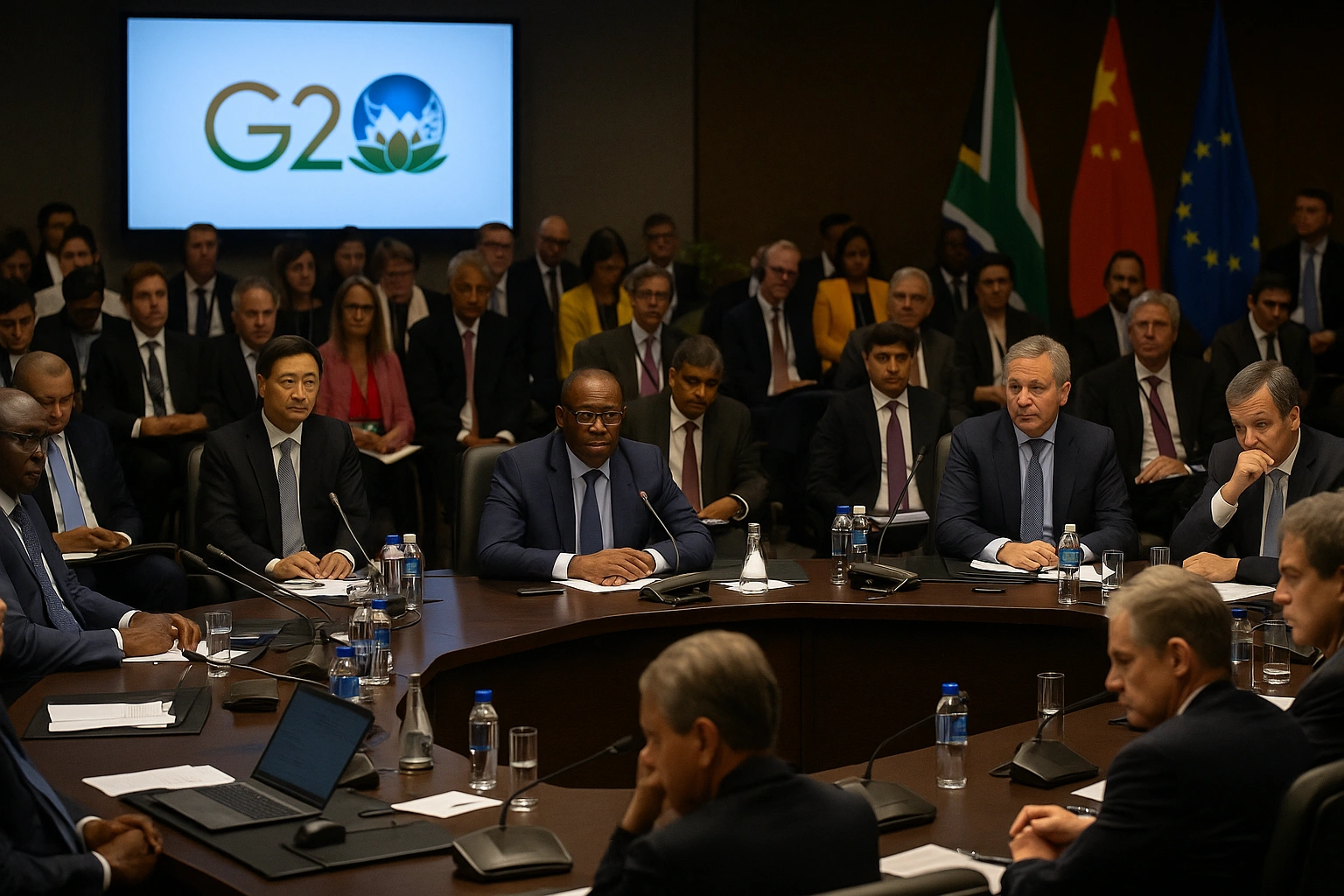

The stakes are as high as they can be as the second meeting of the G20 Finance Ministers along with the Central Bank Governors are to meet in Durban, South Africa. The meeting, which has the theme of Solidarity, Equality, Sustainability, is occurring against the backdrop of increased economic nationalism, the growing danger of tariffs by the United States, and heightened tension in global alliances. As the specter of President Trump‘s proposed trade action hangs overhead and the head of the U.S. Treasury Scott Bessent sits out the table, Durban is quickly becoming a test on whether the G20 can continue operating as the instrument of multilateral cooperation or whether it is shredding itself too thinly to be salvaged any longer.

This week, the U.S. delegation is led by the Acting Undersecretary in charge of International Affairs Michael Kaplan, a clear indication that Washington is dropping to the background in this key discussion. Such a lack of high-ranking representation has prompted many observers to expect G20 to be a toned-down affair with less substance. The ax that hangs over the room is Trump and his ambitious tariff plan: imposing a blanket 10 percent tariff on everything imported, 50 percent tariffs on steel and aluminium, 25 percent tariffs on cars, and talks of even raising duties on life-saving drugs. These interventions, which are likely to further intensify on August 1, will be directed against the BRICS countries and are indicative of the shift to protectionism that is contrary to the G20 principles on which it was established.

The path that this summit is taking has been an issue of concern to Europe, especially Germany. The Finance Ministry of Berlin has been focusing on the topic of intensifying global connections amid turbulent times, though this message now appears to be lost in the noise of disagreement. The U.S. position is not just influencing ties with its old allies, such as the EU, but also risks alienating emerging markets, whose economies depend on liberal trade policies and collaboration-based financial systems. With tariff wars now strangling the supply chain, and investor sentiment low, the world will observe in Durban whether it concludes in substantive commitments or word salad.

Nevertheless, despite the shadow of discord, South Africa is on a roll with a gargantuan, Africa-based program. President Cyril Ramaphosa and South African Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago are arguing the case in favor of solving the most pressing financial problems of the continent: excessive debt burden, climate finance, infrastructure, and digitalization investments. Most African countries are struggling with both 10-percent or more borrowing rates and external debt exceeding $800 billion, equivalent to 45 percent of regional GDP. Conventional sources of finance have dried up; Chinese funding has slowed, and Western donor contributors are prioritizing other global concerns.

To breach the gap, South Africa and its coalition are advocating the reform of the Common Framework of the G20, which has been accused of being sluggish, non-transparent, and biased towards creditors. African leaders are demanding the framework be applied to middle-income economies and revamped for faster delivery of funds. Moreover, there is intensified pressure to activate Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), offering climate-driven investments to aid fossil-to-renewable transitions. Sadly, all these efforts face a bleak future as America is losing passion for climate diplomacy.

A subtle shift in power is taking place, especially within Africa. Members of BRICS Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa have been aligning their financial and trade policies, particularly in response to U.S. protectionism around taxation and regulations. As eight BRICS countries are now included in the G20, they are pushing to introduce alternative payment systems and more independence from the dollar-based financial system. China, specifically, has become a key force in trade and development finance, forming new alliances with nations disenchanted with Western institutions.

China and fellow BRICS states are filling the vacuum left by the U.S., as it withdraws from multilateral cooperation. They are serving agendas that support a rebalanced world order in which the global south gains more voice in commerce, investment, and climate governance. Members of the G20 fear this could result in parallel financial systems, making it harder to coordinate global risks like inflation, climate change, and pandemics.

Still, even amid such shifting dynamics, the G20 has been a platform capable of influencing global stability, provided it can discard internal differences. South Africa is making strong efforts to produce a joint communique, something the G20 failed to achieve in its past year’s summits. A common declaration would be a positive sign of reliability in tackling core issues like climate finance, development, and debt relief the central focus of the Durban agenda. A non-agreement, however, would be a metaphor for deeper malaise, where national interests overshadow collective responsibility.

There is also financial stability under fire. Andrew Bailey, head of the Financial Stability Board and Bank of England Governor, has warned that global growth expectations are being held back by a mix of trade disputes, broken climate pledges, and ineffective policy coordination. The G20 was created to ensure system stability during crises; the risk of currency volatility, capital flight, and sovereign debt default becomes especially acute for vulnerable countries without international cooperation.

There is no shortage of drama or material at this year’s G20 finance summit. Is Durban the moment when Africa finally reshapes the development agenda? Can BRICS emerge as a block powerful enough to counterbalance Western influence? Or will the G20 be rendered impotent by Trump’s trade aggression at a time when it is needed most?

The answers to these questions remain unknown. But one thing is certain: the G20 is in a deadlock. In Durban, there is a chance to transform divergence into dialogue, and paralysis into progress. Should the summit achieve even modest breakthroughs on debt relief, climate finance, or fairer trade frameworks it could revitalize a forum many see as fading. If not, Durban may go down as a turning point, but not a tipping one.