In a more multipolar world, Singapore is skilfully adjusting its foreign policy to safeguard its strategic and economic interests. A significant feature of this realignment is the city-state’s increasing involvement with the BRICS nations, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Historically associated with Western powers and regional alliances such as ASEAN, Singapore’s growing interest in BRICS highlights a realistic shift towards a more diversified global approach. This transition does not signify a renunciation of its Western affiliations but rather serves to enhance them, demonstrating a sophisticated comprehension of the evolving global landscape.

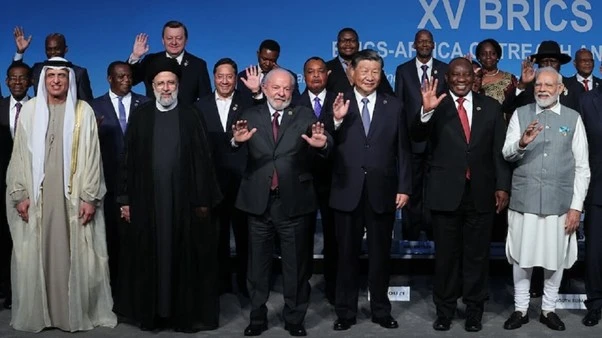

The BRICS bloc, once seen by detractors as a loose assembly of different economies, has evolved into a powerful alliance impacting global commerce, finance, and geopolitical dialogue. BRICS is expanding its reach by including new members such as Egypt, Iran, and Saudi Arabia, therefore establishing itself as a counterweight to Western-dominated entities like the G7 and IMF. Although not a member, Singapore has shown increasing interest in forging stronger relations with the bloc, seeing the strategic advantages this engagement offers in a world no longer dominated by a single hegemonic force.

Singapore’s engagement in BRICS is motivated by many pragmatic factors. Initially, economic diversification is a fundamental element of the nation’s long-term plan. As a diminutive, trade-reliant nation, Singapore must maintain adaptability in response to evolving global trade routes and economic focal points. By aggressively interacting with BRICS countries, Singapore may access new markets, investment opportunities, and alternative supply chains.

India and China are essential to Singapore’s economic future, supported by robust bilateral trade and investment partnerships. Strengthening relationships with these countries via BRICS forums may reinforce Singapore’s position as a regional centre for trade and innovation.

Secondly, Singapore’s shift signifies a calculated endeavour to mitigate geopolitical instability. The escalating competition between the United States and China puts smaller nations, such as Singapore, in a precarious situation. Excessive alignment with any faction might endanger national interests. Singapore maintains its enduring policy of neutrality and equilibrium by interacting with both Western-led and BRICS-aligned organizations. This diplomatic manoeuvre allows Singapore to maintain strategic independence and flexibility in an uncertain global landscape.

Third, Singapore acknowledges the growing significance of alternative global governance frameworks. Entities such as the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) signify a departure from conventional Western financial institutions, providing developing nations with more inclusive and adaptable funding alternatives.

Singapore’s financial institutions and sovereign wealth funds may gain advantages by partnering with the NDB, particularly in sectors that correspond with its green finance and infrastructure objectives. Engaging as an observer or partner nation in BRICS projects will enable Singapore to shape global standards from many perspectives, rather than being restricted to conventional Western paradigms.

Furthermore, Singapore’s shift towards BRICS corresponds with its overarching regional and global ambitions. As a founding member of ASEAN and a staunch proponent of multilateralism, Singapore recognizes the significance of collaborating with other partners to maintain a rules-based world order.

The expanding engagement of BRICS with the Global South aligns with Singapore’s initiatives to promote South-South cooperation and inclusive development. Strengthening relations with BRICS may augment Singapore’s mediation and diplomatic prowess, therefore reinforcing its status as a reliable global interlocutor.

Nonetheless, Singapore’s strategy towards BRICS is expected to remain prudent and measured. The city-state is well aware of the internal disparities among BRICS members and the bloc’s sporadic anti-Western discourse. Singapore flourishes because to stability, the rule of law, and free trade, principles that are not consistently emphasized in the BRICS agenda.

Consequently, its involvement will probably concentrate on practical domains of shared interest, such digital innovation, sustainable development, and financial collaboration, rather than ideological congruence. This strategy guarantees that Singapore may participate in BRICS discussions while preserving its fundamental principles and strategic interests.

Moreover, Singapore’s shift is influenced by internal necessities. As the population becomes more knowledgeable and internationally interconnected, Singapore’s authorities must guarantee that foreign policy yields concrete economic and social advantages.

Increased collaboration with BRICS countries may lead to job creation, knowledge transfer, and investment prospects that align with the interests of Singaporeans. Moreover, as Singapore establishes itself as a worldwide centre for arbitration, fintech, and climate financing, partnership with BRICS nations might augment its significance in these areas.

Singapore’s strategic shift towards BRICS exemplifies its flexible and progressive foreign policy. In a fragmented and realigned global landscape, Singapore opts for participation rather than alignment, and pragmatism above dogma. By fostering relationships with BRICS while preserving robust connections with old allies, Singapore is not only safeguarding its economic future but also promoting a more inclusive and equitable global order.

The efficacy of this plan will hinge on the city-state’s capacity to manoeuvre intricate geopolitical dynamics while adhering to its core ideals of transparency, rule of law, and international collaboration. As the global centre of gravity shifts, Singapore’s strategic engagement with BRICS may emerge as a pivotal achievement in 21st-century diplomacy.