With women facing major institutional and cultural obstacles influencing their participation, career paths, and economic destinies, Turkey’s labour market stays fundamentally gendered. Although during the past few years the nation has made progress in increasing women’s access to public life and education, many Turkish women still have a difficult path from educational accomplishment to significant labour market engagement. This gendered labour dynamic not only inhibits women’s personal economic empowerment but also impedes the nation’s more general social growth.

Turkey’s female labour force participation rate is among the most striking markers of gender inequality; although rising, it still trails far behind the OECD norm. Comparatively to several European nations, less than 35% of Turkish women work as of recent years. This disparity points to a constellation of obstacles including cultural standards, inadequate support for childcare, and strict labour restrictions unable to fit family obligations. Often making it harder for women to obtain or stay in official employment, traditional gender roles nevertheless assign main caring and home tasks to women.

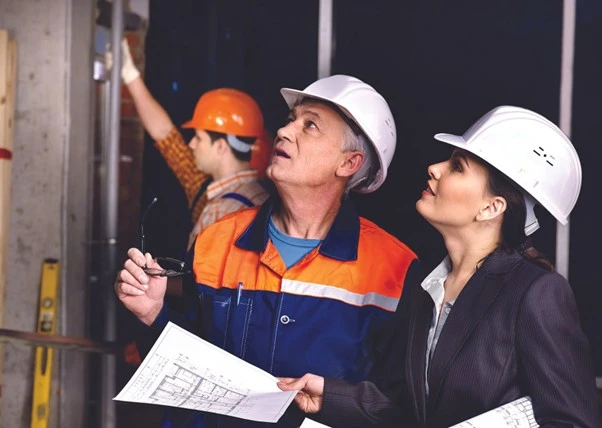

Sectoral separation aggravates female inequity even more. Turkish women are disproportionately found in low-paying, casual, or unstable employment, such as domestic service, agriculture, and textile manufacture, where labour rights are few. High-paying and high-status industries including engineering, banking, and executive management remain male-dominated meantime. This occupational sorting reflects gender presumptions about “appropriate” occupations for women and ongoing discrimination in hiring and promotion policies, not just an issue of education or skill.

Notwithstanding these obstacles, education has been a great vehicle for transformation. Over the past two decades, the gender difference in school attendance has closed significantly; now, Turkish women graduate from colleges at higher rates than ever before. Still, the improvements in education have not exactly matched fair job results. Many highly educated women find themselves either underemployed or unemployed, either because of prejudices that devaluate their credentials or reluctance among companies to hire women who might take maternity leave or emphasize family duties.

The “motherhood penalty,” a well-documented phenomena whereby women with children earn less and advance less in their careers than their male or childless female peers, adds still another layer to Turkey’s gendered labour market. Given the dearth of reasonably priced childcare facilities and the societal assumption that mothers should be the main caregivers, this penalty is especially severe in Turkey. Many women so find themselves driven into part-time or informal employment or drop out of the workforce totally following motherhood.

Some of these discrepancies have been tried to be addressed by government policies with varied results. Though they exist, programs providing maternity leave, economic benefits for families, and vocational training for women usually fall short of tackling the underlying reasons of gender inequality. Furthermore, while well-meaning, laws meant to safeguard female workers, such as early retirement options or restrictions on night shifts, may unintentionally support preconceptions and hinder women’s prospects in the workforce.

The private sector is also rather important in either supporting or questioning gender roles. Although some progressive businesses have instituted mentoring programs for women, flexible working schedules, and gender diversity policies, these are not yet common practices. Efforts to build inclusive workplaces are further hampered by the dearth of women in corporate leadership. Among the extra challenges female entrepreneurs encounter are legal or bureaucratic obstacles, lack of networks, and inadequate financing.

Positively, a younger generation of Turkish women is questioning the norm. Women are starting businesses, fighting for equal rights, and lobbying for legislative changes supporting gender parity in work ever more often. Women’s voices have been raised by social media and civil society action, which also highlights pay differences, discrimination, and workplace harassment. Demanding structural change, movements as #KadınCinayetleri (femicide awareness) and campaigns for equal parental leave have pushed these concerns into the national dialogue.

Systematic adjustments are needed if Turkey is to really improve its labour economy and fully use its female population. These include increasing access to quality, reasonably priced childcare; encouraging shared parenting; changing labour rules to better enable remote and flexible work; and tackling biassed hiring practices.

Beyond classroom instruction, educational programs should include training on gender sensitivity for businesses and employees both. Future-proofing the workforce also depends on more investment in women-owned companies and aggressive initiatives to integrate women in industries including technology and innovation.

Turkey’s labour market’s gender distribution is not only a women’s issue; it is a national economic one as well. Research studies repeatedly reveal that labour markets inclusive of women are more robust, creative, and productive. Closing the gender employment disparity will boost Turkey’s GDP and help families all around to be better off. Reaching this need for not only legislative changes but also a cultural transformation redefining gender roles and acknowledging the whole worth of women’s economic contributions.

Turkey is at a crossroads in essence. The decisions it takes now on gender equality in the workforce will determine not only the course of Turkish women but also the social and financial path of the country overall. Breaking down labour market barriers is not only a question of fairness; it’s also a necessary first step toward a more dynamic, inclusive Turkey.